The Craft of KidLit: Author Interviews

- Jun 20, 2022

- 9 min read

In this series of posts, I aim to shed light on the creative process of KidLit by asking a wide variety of authors the same set of ten questions. Check this space to gain insight and perspective on the craft of writing for kids.

DIANE MAGRAS

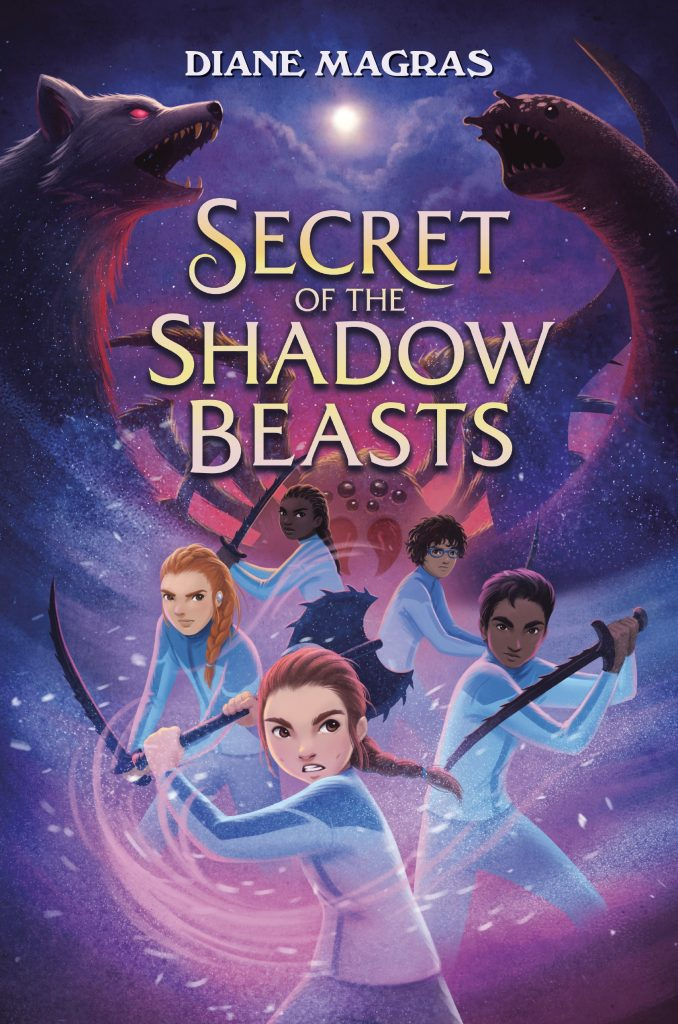

Author of the The Mad Wolf's Daughter and its sequel The Hunt for the Mad Wolf's Daughter, as well as the newly released Secret of the Shadow Beasts.

1. What initially inspired you to write for kids, and what motivates you to continue to write for that audience?

I’ve been a writer since my teens, but I never wrote for kids until I was an adult and my son was in third grade. He’d just begun reading middle grade fiction, and I was reading it too in order to talk books with him. I was blown away by how vivid, powerful, hopeful, yet real these books were. I fell in love with this kind of fiction. Thus inspired, I wrote the first draft of The Mad Wolf’s Daughter, which became my debut. I was certainly, in part, writing it for my son (he was my reader throughout the process and gave me excellent support and critical feedback). But even as my son has outgrown my books, I continue to write for this audience because I love what these books do. I remember what it’s like to be a kid on the cusp of adolescence, and how hard those years are. I love writing young characters who achieve great things. Kids these days deal with everything I dealt with and more. So I write for them. I hope they can find friends in my books, and escapes, and something to think about too.

2. Give us a peek into your brain before you've settled on a project. How do ideas come to you, and how do you begin once you’ve got a great one?

Far too many ideas come to me! I usually have three or four contenders at any one time. But when one is going to work, it’s spent some time in both my brain and my notebooks. When I’m ready to start thinking about an idea seriously, I sketch out a basic concept and write a premise. If it’s a fantasy, I write the details of the world. And then I sketch out my major characters, usually pretty intense psychological portraits, though sometimes I’ll just write a quick scene and see if they come to life. If it doesn’t feel right after this point, I’ll give it a break, and mull over other ideas and see if the initial one will come back to me. Sometimes I need a break to figure out how to make it work. For my most recent book, Secret of the Shadow Beasts (which just came out), I had a concept I’d been pondering but put aside; then one day I thought of a twist that made it work.

Once I’m pretty sure I have a good idea, I write the first couple of paragraphs in my notebook. Sometimes, if I’m feeling really confident, I’ll just open a file on my computer and do it there. If I have a good sense of the story, I may even start the novel. While I always know the beginning, some of the middle, and the end, I’m really just an organized pantser; I need to write the story to see where it will go.

3. How much is your chosen idea for a story influenced by what is "marketable"?

These days, the market influences my choices considerably, but in a healthy way. I read a huge amount of middle grade fiction and take notes, analyzing what I think worked or didn’t work as a story, and what I think readers might respond to. This helps me understand what books are being published, how they’re appealing to readers (including the important first readers of my genre: teachers and librarians), and, in general, what the fictional landscape looks like. I don’t chase trends but look at the big picture and search for patterns.

Within this landscape, I’m my own writer; my works will always have my own voice and my own brand. So while I pay attention to what’s being published and what’s being widely read, I use that as inspiration to write the stories I want to write. Sometimes my stories dip into a known genre—for instance, Secret of the Shadow Beasts pays homage to “school story” fantasies—but they always follow my own priorities.

There’s a delicate balance in this: writing for the market while also writing for yourself. Be original, but be recognizable too. I’m more comfortable with this now than I was five years ago.

And really, this is less scary than it sounds. Writing the kinds of books that are being published simply means knowing the market. Everyone needs to do this to some degree. And—though there are exceptions—in general, if you don’t pay attention to what’s out there, you’ll probably have difficulty getting published.

4. How detailed does your outline get? Do you leave space for changes, or are plot points written in stone?

My “outline” for my first draft is a series of long paragraphs in my notebook, more of a synopsis or concept. I tend to write pages and pages of it (character sketches, details of the setting, even a scene or two), but it’s not what anyone would call a traditional outline.

All of this—plot points, characters, even major chunks of the story—are always up for adjustment. I discover my characters as I write. While I always start with a premise, a climax, and an ending, the unforeseen difficulties and opportunities I put in their paths to reach every one of those points come naturally as I’m writing.

Once I finish the first draft, though, I write a detailed outline. That outline serves as a big-picture guide as I revise. But even then, as I revise, I’m willing to change plot points. Sometimes I even change the ending if I think of something that serves the story better.

5. What's your personal technique for connecting to the younger person inside you and writing from that place?

I’m very fortunate in that I’ve had a lot of interaction with kids. This helps me get into the “zone.” Sometimes as I’m writing, I picture my readers and think about what they’d find exciting, funny, and compelling. If I can get into this mindset, the narrative flows. When I’m struggling to find that place, I focus on the kid I’ve known best—my son—and think about what he was like when he was the age of my characters.

If you don’t have easy access to kids, though, there’s another way to get there: Read a lot of middle grade novels. I do that as well, as that helps me considerably when I’m stuck. (Like students, I have my mentor texts, including ones I use for voice.)

And follow teachers on Twitter. You’ll see a lot of amazing student projects, see what students are reading, and get a sense of what matters to kids all over the country.

6. What are three or four books you would tell any writer to read who wanted to write middle grade? Why?

The Shape of Thunder by Jasmine Warga is a wonderful model of how to write about a tragedy for a young audience. It’s realistic fiction, and Warga’s kids and adults feel completely real (her kids have distinct voices, make mistakes, and grow; and her adults make mistakes too, just as adults and parents do in real life, but rarely do in this genre). Its subject is heartbreaking—a school shooting and how two former friends come to terms with who they lost and how it happened—but the warmth ensures that it’s never completely bleak. It’s a great example of how to balance those elements.

Fighting Words by Kimberly Brubaker Bradley also deals with an incredibly difficult subject—sexual abuse—and is written beautifully. The plot depicts how its protagonist and her sister heal from their experiences. And while there is terror in the story’s current timeline (the protagonist’s sister attempts suicide), the narrative is gentle and the narrator’s quirky voice ensures that the reader can deal with it. This book is a class in how voice can not only hook a reader but take care of a reader too.

Cuba in My Pocket by Adrianna Cuevas is a marvelous historical fiction with fully-fleshed characters and a fast-paced narrative. It begins in Cuba, with danger always present, and follows the narrator’s escape to the U.S. by himself. Cuevas balances his loneliness and worry with hope and warmth (again, warmth, which I feel is necessary to a successful middle grade novel). This book shows how to build tension in a historically accurate world with an equal balance of despair and hope. That’s a very difficult balance to maintain.

The Luck Uglies by Paul Durham is an older book now (it was one of the middle grade novels that convinced me to start writing middle grade fiction), but remains a highly inventive and tremendously engaging fantasy. It’s the story of heroic villains, scary but not-always-evil monsters, brutal rulers, warm-hearted villagers, and a group of scrappy kids ready to break any rule in order to do what’s right (or what they consider to be fun). It’s a beautifully imagined work with a pitch-perfect voice for this genre. It’s another great example of voice, as well as how to write a fresh, charming fantasy with important themes.

7. How do you involve outside readers in your process? Do you keep your work to yourself? Do you share it with any kids to get their take?

My first two books went through my son multiple times, and an early draft of my current did as well. But for the next, I don’t think I’ll have a young reader in the house (he’s in high school and reading YA), which is hard. There’s nothing like calling over to another room, “What do you think of this plot/character/paragraph?” and getting instant feedback. But my husband is a book critic of fiction and nonfiction for adults, and he always reads an early draft. I have a variety of other readers I rely on, some one-time critique partners and a few long-term ones.

When I get feedback from anyone, I make a list of their comments in a Word file. Then I put my own comments into that file with my suggestions of how I’ll address their comments. Sometimes, though, I need to dive back into the manuscript and try something to see if it’ll work.

Sometimes I don’t take suggestions. That’s usually when I disagree about some element of storytelling or my vision for the novel. If someone tells me that a character isn’t fully-fleshed, for instance, or a plot point doesn’t make sense, I pay attention.

I prefer it most when people just tell me that. Though some suggestions are good, it’s much easier for me to remain true to my story if I don’t use other people’s solutions.

8. Do you start with character or plot, or do you see them as indistinguishable? Why?

For my first two books, I started with character. I knew who my protagonist was and created a story around her (it fell into place quite rapidly). For my third, I started with a world and a story, though I had a sense of who my protagonist would be early on. It really depends on the novel. Sometimes a plot comes to mind, and I’ll populate it with characters I’ve already thought about. Sometimes I’ll mull over a character and build a story around them. I do think there’s a big difference, though, in the kind of work that comes from those two approaches. For Secret of the Shadow Beasts, which is more of a plot-initiated story, I was able to see the meaning of the story quite early, as well as populate it with psychologically rich portraits of characters beyond my protagonist. My character-initiated books rely heavily on my protagonist’s voice, dreams, and greatest fears. It’s wonderful to feel those in your bones when you begin, as those are among the most important things to know about your protagonist and story, and it takes a lot longer to nail those when you start with a plot.

9. What about writing KidLit frustrates you? To put it another way... What are some of the roadblocks you encounter that are specific to writing for kids?

Most of my roadblocks have come with publishing, not the writing itself. And they’re issues that many authors writing for many different audiences deal with: long delays, rejections (which will never stop hurting), and things like that. Writing for children and interacting with teachers, librarians, and students has been the most pleasurable kind of writing I’ve ever done.

10. What are you working on now? If you’re at a point where you feel comfortable sharing the information, what inspired the project?

I’m afraid I’m one of those authors who can’t share anything about works in progress! Apologies!

Diane Magras is the award-winning author of the New York Times Editors’ Choice The Mad Wolf’s Daughter, as well as its companion novel, The Hunt for the Mad Wolf’s Daughter. The upcoming Secret of the Shadow Beasts is her third book. An unabashed fan of libraries (where she wrote her first novel as a teenager), history from all voices, and the perfect cup of tea, Diane lives in Maine with her husband and son.

And here’s some links:

Website: https://www.dianemagras.com/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/dianemagras

Comments